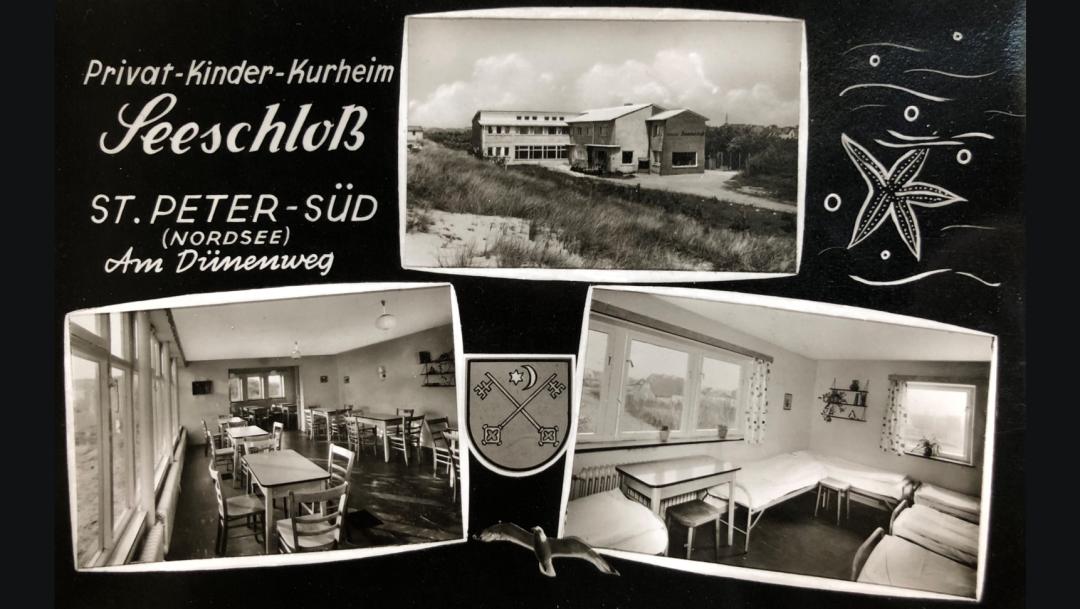

This is a postcard from Privat-Kinder-Kurheim Seeschloβ, the children's home run by a former Nazi officer. Professor Ilona Yim was sent to live there for five weeks when she was 8. Inset photo of Ilona Yim by Christine Parales Porciuncula.

Millions of children experienced untold psychological damage

When the former Nazi officer Hugo Kraas spoke, an 8-year-old Ilona Yim shivered.

The year was 1979 and the former SS commander was in charge of a children’s home, where Yim was sent to live for five weeks.

Kraas welcomed the young residents by telling them to behave and follow the rules, which included not speaking during nap time or at night, changing clothes only once a week and lying to parents about their experience.

Yim’s day consisted of two four-hour hikes with a four-hour nap in between. She cried every day. The frightened girl watched fellow children dragged from their beds and put into cold showers as punishment for talking when they were supposed to be sleeping. Though the children were allowed to write to their parents once a week, their letters were censored.

Yim’s day consisted of two four-hour hikes with a four-hour nap in between. She cried every day. The frightened girl watched fellow children dragged from their beds and put into cold showers as punishment for talking when they were supposed to be sleeping. Though the children were allowed to write to their parents once a week, their letters were censored.

“You were not allowed to say anything critical or else they wouldn’t send the letter,” Yim recalls. “So, it creates in a kid this situation where you have to say something nice about people who were really being abusive to you. That really messes with your mind because they make you lie to your parents. And, I think that also contributed to people not talking about it when they came home because if you do, you have to preface the conversation by saying, ‘by the way, I just lied to you all these weeks and it wasn’t great.’ It was miserable.”

Yim, now a UCI professor of psychological science, was one of millions of German children who were sent away to children’s homes from the 1950s through the 1980s. An estimated 8-12 million youth went to those homes, often far away, to “get healthy” for six to 12 weeks. They were sent on the recommendation of doctors or other authorities and public health insurance paid the bill.

“Many of the children were not even ill,” says Yim, who was sent away for being underweight. “The weeks of separation from parents and the conditions in the homes were extremely stressful and traumatic for many children. As one of the affected children and as a scientist who has studied stress and health for the last two decades, I can speak to these issues both through a personal and a professional lens.”

She is speaking up now to raise awareness about what happened so it won’t happen again.

Yim has partnered with the Verschickungskinder (German for sent-away children), a survivors initiative to raise awareness, and she serves as one of the lead researchers.

The organization’s website includes more than 2,000 testimonies, recalling feelings of homesickness, strict bans on parent visits, censorship of letters, rigid rules, extreme and often cruel punishments, as well as far-reaching health and psychological consequences later in life.

For example, victims tell about being force-fed awful porridge, being strictly forbidden to use the bathroom at night, having to wear the same underwear for an entire week and being bullied by fellow children, who were encouraged to bully by the home staff. They also testify that parents didn't believe them when they told the truth about their experiences, which contributed to their silent suffering.

More and more sent-away children have begun to publicly speak about their traumatic experiences in the homes. And, Yim’s research lab recently launched its first empirical study on the effects of the “sent-away” experience on the health, well-being and social relationships of those affected.

Yim’s research is finding that the long isolation from parents and the often-abusive treatment sent-away children received left emotional scars and health problems that remain present decades later.

“I want to see an acknowledgment that this really happened and broad societal awareness,” Yim says. “We need to know about this experience and the consequences so that this will never happen again.”

— Mimi Ko Cruz