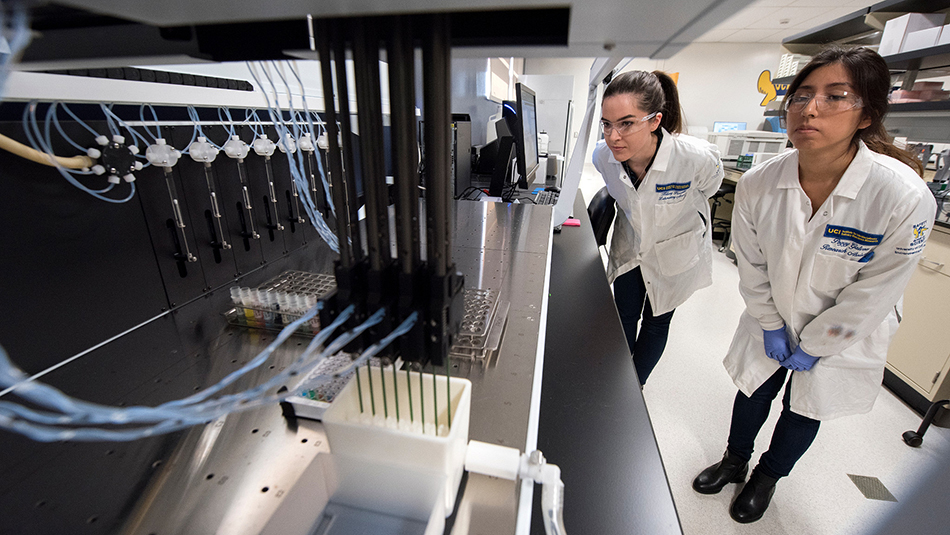

Institute for Interdisciplinary Salivary Bioscience Research laboratory manager Hillary Piccerillo (left) and former lab technician Peggy Galvez oversee the robotic transfer of saliva from collection tubes to test plates for an experiment. Photo by Steve Zylius. Photo of Jenna Riis by Patricia DeVoe.

IISBR researchers champion the use of spit in diagnostics

By Matt Coker

The so-called “diagnostic fluid of the future,” saliva is loaded with DNA, enzymes, hormones, immune system markers and other substances that make it a minimally invasive alternative biospecimen to blood for a dizzying array of medical, nonmedical and even commercial uses.

However, expertise is required to decipher biomarkers, many clinicians still do not collect saliva samples, and “spit science” research can literally be all over the map. That’s where UCI’s Institute for Interdisciplinary Salivary Bioscience Research (IISBR) comes in.

Co-directed by Jenna Riis, assistant professor of psychological science, and Michael Hoyt, a clinical and health psychologist and associate professor of population health and disease prevention, the IISBR conducts salivary bioscience research and educates, trains and consults researchers, physicians, caregivers, veterinarians, psychologists and other professionals on collecting and analyzing spit samples.

Co-directed by Jenna Riis, assistant professor of psychological science, and Michael Hoyt, a clinical and health psychologist and associate professor of population health and disease prevention, the IISBR conducts salivary bioscience research and educates, trains and consults researchers, physicians, caregivers, veterinarians, psychologists and other professionals on collecting and analyzing spit samples.

“IISBR serves as a hub of scientific collaboration and support,” Riis says. “It brings together investigators at all levels of training – from undergraduate students to experienced scientists – and from a wide range of disciplines, including medicine, public health, psychology and environmental health. And IISBR fosters rigorous research via a team-science approach. This is the most important and valuable contribution of IISBR as it helps advance knowledge while also promoting innovative interdisciplinary research and facilitating unique training and education opportunities.”

Hoyt adds that the institute is “involved in projects that come in from all over the world. We have different functions that fall under our umbrella. One of them is to provide consultation, expertise and laboratory services for people doing this work, particularly folks from across the UC, but really from all over.”

He finds it particularly “exciting that the institute has drawn attention from scholars all around UCI. We have professors who come through who really run the scientific gamut. I have a medical oncologist doing work on dietary changes with her patients, and we have people who study how metals in the environment get into people’s bodies. We have other folks doing neuroscience work. It really does draw from different disciplines. It’s anyone who’s looking for a window into the body.”

Among those seeking such a window is Riis, who researches the etiology of health disparities and the processes by which environmental factors and social experiences affect child development and lifelong health.

“Salivary bioscience is central to this work as it allows me to examine the body’s response to adversity by looking at changes in multiple physiological systems dynamically across time and with minimal burden to my participants,” she says. “Salivary biomarkers also allow me to examine environmental exposures – such as to pollutants, toxins and viruses – and their effects on mental and physical health.”

The director of UCI’s Behavioral Medicine Research Lab and editor-in-chief of the International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, Hoyt studies how individuals adapt psychologically and biobehaviorally to chronic illness, particularly cancer.

“When we say ‘biobehavioral,’ we’re starting to talk about the word ‘mechanisms,’” he explains. “What are the pathways between psychological and social factors and their impact under the skin? What’s between the two dots that we’ve been connecting? Maybe those things are more social, more psychological, more emotional, but they also are biological. And so we’ve learned a lot about things like stress pathways and immune system pathways that connect mind and body. Psychologists and behavioral researchers have come a long way in integrating this knowledge and recognizing that our interventions and treatments can alter those pathways to lead to better health outcomes.”

Hoyt says that salivary bioscience is becoming more integral to the field.

“We’re taking a biobehavioral approach to cancer survivorship,” he says. “For a long time, we’ve tried to understand different types of cancer-related outcomes – such as fatigue, depressive symptoms, the ability to pursue life goals, chronic pain, cognitive changes, sleep problems, these kinds of things – and we’ve done decades of research to understand the role of psychosocial factors like social support, relationships and our emotions. We can do this, in part, by using salivary bioscience as a window to biological processes.”

He’s hopeful that saliva will inform his current work with young adult cancer survivors.

“Psychologically, you can imagine how difficult it is having cancer come into their lives at a very unexpected time – and a very disruptive time developmentally,” Hoyt says. “So I’ve been testing an intervention we’ve developed with young adults with testicular cancer after chemotherapy. It’s focused on how we psychologically and socially help young men with testicular cancer understand what’s important to them, how to pursue their goals, how to adjust post-cancer and how to regulate emotions that have come because of their experience with cancer.”

This research involves careful measurement of stress and immune system biomarkers from saliva to learn if and how UCI’s clinical intervention affects cancer-relevant biology as well as symptoms such as depression and anxiety.

“Saliva is a very encouraging window because it’s easy to get to,” Hoyt says. “It’s not invasive. We don’t have to stick someone with a needle. You know, COVID furthered the dialogue. People get it now that collecting saliva is better.”

However, he cautions, interpreting specific biomarkers requires expertise that’s mostly confined to labs and health research entities such as UCI Health. And it will take additional research to make saliva-based measurements more useful in clinical settings.

“We need to move up what we call the translational spectrum,” Hoyt says. “We need to understand when it’s time to integrate these kinds of things into clinical practices.”

Further translational research requires spreading the word and building relationships among scholars and practitioners across disciplines as well as the campus, the health system and beyond – which is another role of the IISBR.

“You’ve probably heard the term ‘team-based science’ a thousand times,” Hoyt says. “You can’t do anything anymore – you shouldn’t do anything anymore – without understanding how different disciplines fit together. If you aren’t thinking that way, you’ve probably missed something. So when we start talking about these biological mechanisms … gosh, I couldn’t do this without reaching across all the aisles, if you will. I couldn’t do this without talking to my medical collaborators, with my immunology colleagues, social scientists, public health professionals, my biology folks. It takes that team.”

He’s inspired by the direction salivary bioscience is headed.

“We’re starting to look at things like genetic changes that we can see and test in saliva that may put patients at particular risk for poorer outcomes,” Hoyt says. “We’re testing this intervention and using saliva measures to really see what kind of impact we’re having on the biology that might underscore some of this.”

He encourages clinical researchers around UCI and in various fields “to celebrate the potential these markers have in answering our questions and to start thinking about the utility of saliva in their own work. There are many windows into the body. This one just happens to be more easily accessed. And that’s what gives it so much potential.”

Riis wholeheartedly agrees.

“The range of analytes that we can measure in saliva is rapidly expanding,” she says. “We can already look at markers from multiple systems, including stress and sex hormones, markers of immune function, and genetic and epigenetic indices. Also, because saliva can be self-collected in the field, salivary bioscience provides unique opportunities to learn about the health and well-being of communities in real time – making the potential application of salivary bioscience to health surveillance, monitoring, assessment and interventions very exciting.”

IISBR’s summer Spit Camp

Faculty, post-doctoral scholars and fellows will attend IISBR’s Spit Camp Aug. 10 and 11 on campus in Social Ecology 1. Core IISBR faculty will lecture on theoretical perspectives, use of oral fluid as a biological specimen and strategies for writing papers, presentations and proposals. A laboratory component provides hands-on, supervised training on sample processing, salivary immunoassay and kinetic reaction assays. An optional third day on Aug. 12 features Riis leading attendees in lecture and guided practice with real salivary data. More info: https://iisbr.uci.edu/spit-camp-1/.