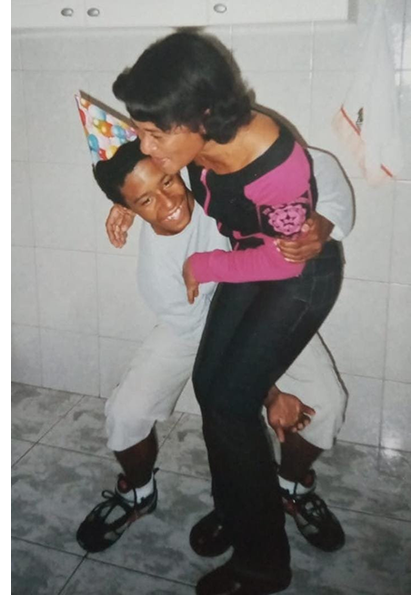

Eraldo Souza dos Santos' essay about his mother's enslavement is nominated for a Pushcart Prize. He is turning her story into a family memoir with support from three prestigious residencies. Inset photo is dos Santos as a youngster with his mother in Brazil.

Dos Santos recognized for work on memoir

When Eraldo Souza dos Santos’ Brazilian mother Nilva Moreira de Souza was 7 years old, her sister sold her.

It was 1968 when she disappeared. Her sister, too, fled home and didn’t tell anyone what she had done until she was caught years later and forced to confess, leading police to the family who bought de Souza.

She was found some 500 miles away in a home where she was forced to work for a white family as a nanny, housekeeper and farm hand. Dos Santos’ grandmother refused to press charges against her white adopted daughter for selling her sister or the family who bought her, and she forbade any mention of the complicated saga.

She was found some 500 miles away in a home where she was forced to work for a white family as a nanny, housekeeper and farm hand. Dos Santos’ grandmother refused to press charges against her white adopted daughter for selling her sister or the family who bought her, and she forbade any mention of the complicated saga.

But dos Santos, assistant professor of criminology, law and society, learned his mother’s story when she first told him about it decades ago.

Today, he is working on telling the world.

His mother’s traumatic experience caused long-term damage to her mental well-being and he hopes that sharing her story will encourage others to come forward with the goal of ending modern day slavery.

“Everything started during the pandemic in 2020 when I realized my mother was suffering from paranoia,” dos Santos recalls. “It’s a consequence of her enslavement that she cannot trust people. She was sold into slavery and she could never forgive my aunt. And, she couldn’t forgive my grandmother for making her live in the same house with the person who sold her when she returned after years of enslavement.”

The compelling story has been published in parts in magazines, and now, dos Santos is working on her memoir, which he is co-authoring with de Souza.

The book, dos Santos says, “is an (auto)biography of my illiterate mother and a meditation on the lived experience of Blackness and enslavement in modern Brazil.”

By weaving in extensive archival research and interviews, he explains, the book will narrate “our journey to Minas Gerais, where she was born and where German and Swiss colonization historically contributed to the persistence of forced Black labor, and Bahia — the Blackest state in Brazil, where she was enslaved for years — to investigate why the family that bought her has never been brought to justice. It also narrates my grandmother’s journey to find her missing daughter amidst one of the darkest moments in Brazilian history.”

Dos Santos’ book project is already receiving recognition.

He has been awarded three prestigious artist residencies — from Yaddo, the Blue Mountain Center and the Kimmel Harding Nelson Center for the Arts — taking place this summer. For Yaddo, he will spend five weeks this summer working on his family memoir. For Blue Mountain, he will spend several weeks working on a one-act monologue based on the memoir in an effort to reach a broader audience, especially those who are illiterate. He will continue working on the play while in residency at the Kimmel Center.

Meanwhile, two of Dos Santos’ essays — “Everything Disappears” (The Decolonial Passage) and “She Is There” (Inkfish Magazine) — have been nominated for a Pushcart Prize.

Excerpts from “Everything Disappears,” written from interviews with dos Santos’ mother:

Ai, Eraldo, I think people have always made me a slave, in one way or another. After so many years, how many?, I don’t remember… Dona R. arrived at the puteiro and asked your aunt: Where is Nilva?

…Every night they would take a piece of an old mattress and put it in that little corner of the room for me to sleep on it. There was only room for my feet if I shrank down, and I didn’t have a pillow.

I don’t remember what they all looked like. Up until I was 20 or 21, I could remember their faces perfectly. Today I only see shadows. No, I don’t remember their names. Everything disappeared from my mind. But if I close my eyes now, I can see your aunt’s face perfectly.

…The bad thing was that it wasn’t just looking after the children. They put me in charge of waxing the whole house, too. Especially a large room where they kept things like old furniture. This room was also used as a garage. I used to clean all the house on my knees. That’s why, when your grandmother found me, my knees were so bruised, dark, to the bone. I never understood why they always asked me to wax everything all the time. I would put the wax on the floor, and the Black maid would wax it. The waxer was too big for me.

…I never understood why your aunt didn’t come back to pick me up from there.