Students raise awareness of crimes of the state via TikTok for criminology class

By Matt Coker

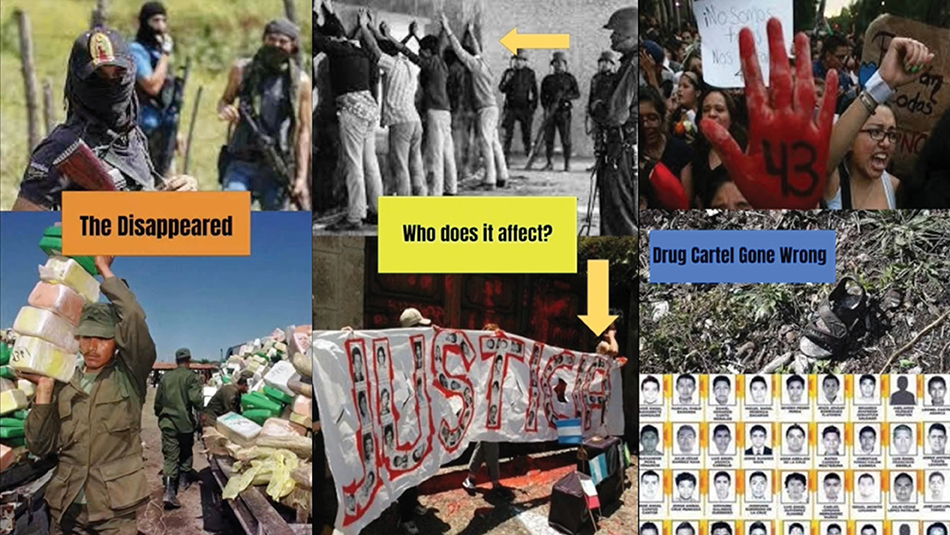

Still images of Mexico’s flag, street protesters, student mugshots, an empty jail cell, armed forces in fatigues and men lined up against a wall fill the screen as narrators describe the plight of our southern neighbor’s “disappeared.”

We hear the voice of a young woman explaining that 90,000 people are missing in Mexico, including 43 college students who vanished in a single day. Viewers of the short documentary go on to learn that the country enacted a toothless law that has done nothing to bring back the missing.

We hear the voice of a young woman explaining that 90,000 people are missing in Mexico, including 43 college students who vanished in a single day. Viewers of the short documentary go on to learn that the country enacted a toothless law that has done nothing to bring back the missing.

“The friends and families of the 43 missing students, as well as the thousands of other disappeared victims, should not have to wait any longer to find out about their loved ones’ whereabouts,” we hear another young woman say at the film’s coda. “They cannot do this alone, nor should they. It is time for the international community to seek truth and justice.”

The preceding was not screened for a news program, a global fact-finding mission or a non-government organization’s sizzle reel. Posted on TikTok, the wildly popular social networking service owned by a Chinese company, the documentary was presented by its student creators as one of dozens of finals projects for UCI’s Crimes of the State class.

Small groups drawn from the winter quarter’s 110 enrollees collaborated on presentations that addressed such issues as femicide in Latin America, the torture of Syrian refugees, genocides in China, Darfur and Myanmar, and violence against South African women and anyone in the crosshairs of the Taliban in Afghanistan.

Formally listed as “CRM/LAW C100. Special Topics in Criminology, Law and Society,” which indicates the elective course’s content varies with the interest of the instructor, Crimes of the State is taught by Nicole Iturriaga, assistant professor of criminology, law and society. Her research interests are science and technology, political sociology, social movements and human rights, which are entirely represented in Crimes of the State.

“We watched some Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International videos to show them what they should be going for,” Iturriaga says of her students. “That way they had kind of a model.”

TikTok was also a vehicle used during her fall quarter Science, Technology and Society class. Students filmed themselves asking random students around campus hypothetical questions about surveillance technology. The footage was then posted on TikTok.

“The thing with TikTok is, I really like TikTok,” Iturriaga says. “I think it’s fun, and you can get so much information in three minutes ... when done well.

Her students have also had the option of presenting their projects as podcasts or via PowerPoint. “My belief is you need to know how to present information as an adult in the real world,” she explains.

The winter quarter class was online-only due to the pandemic, but Iturriaga looks forward to teaching Crimes of the State in person. “I think it will be easier,” she says. “It will be more fun, but I also think that having an audience for the presentations will put a little more pressure on students to take them seriously.”

She is also exploring the possibility of incorporating other forms of mass communication into her classes. “I may offer up if they want to do music or something else that leads to more creativity—while also being aware that may not be everyone’s jam. Maybe not everyone wants to do a TikTok. So, I will play around with it. I also asked the students for input on what worked, what didn’t work and any suggestions on how to make it better.”

She has found that “for students who want to lean in, it’s a very good class. For the others, it’s, ‘Oh God,’” she says with a laugh. “There are some students who are way savvier than others on how to do this very well. In the fall, I had one student who was already kind of a big TikTokker and got over 1,000 views of his video.”

Iturriaga, whose book “Exhuming Violent Histories: Forensics, Memory, and Rewriting Spain’s Past” was recently released, concedes Crimes of the State is “a very heavy class” due to the sobering subject matter. “I end every class with an uplifting quote and tell them to be kind to themselves and others.”

She adds, “It is not an easy class in terms of content. But I think the students who got the most out of it had to be open and vulnerable to these complex and complicated concepts. They had to be pushed a little bit into what their own ethics are in terms of how they understand human rights. This was a very great, very talented group of students. I’m grateful I got to teach them.”

The timing of the winter quarter class was unique. “The Ukrainian war happening was fortuitous, in an unfortunate way, because we had just been talking about all this stuff, and then we were able to put it into practice,” Iturriaga says. “One presentation was about the Geneva Conventions in relation to the Ukraine. I learned something totally new.”

She hopes her students learn something new as well.

“I think it’s important for everybody, especially college students, to understand how fragile human rights are. If that can inspire the defense of human rights, then I think I’ve done my job.”