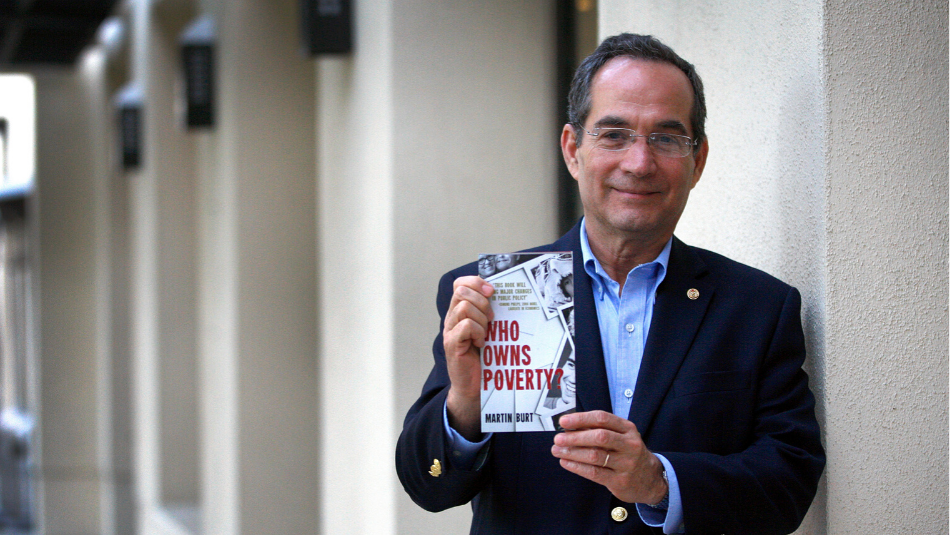

"We are all poverty and not poverty in our own unique ways." — Martín Burt. Photo by Karen Tapia

Distinguished Professor Martin Burt’s paperback advances new approach to tackling indigence

By Mimi Ko Cruz

People who are impoverished are the experts on poverty. And, they are the ones governments, development organizations, charitable agencies and policymakers should be consulting to reduce poverty, according to “Who Owns Poverty?” (Red Press Ltd., 2019).

The new book, by UCI Distinguished Visiting Professor Martín Burt, executive director of Fundación Paraguaya, a nongovernmental organization that advances microfinance and entrepreneurship in the South American country, and former mayor of Paraguay’s capital city, Asunción, where a third of the population is impoverished, outlines Burt’s Poverty Stoplight, a new app that allows families to assess their level of poverty and identify strategies to overcome their specific needs.

The app is a tool divided into 50 indicators across six dimensions:

- income and employment,

- health and environment,

- housing and infrastructure,

- education and culture,

- organization and participation, and

- interiority and motivation

The indicators include questions such as whether families have savings, healthy teeth, a modern bathroom, school supplies, hobbies, emotional control, a phone, a safe home, vaccinations, good nutrition and control over life decisions. The families select from three traditional stoplight colors which point to their level of poverty on each indicator. Green means lack of poverty, yellow means poor and red means extremely poor. Each indicator is adapted to each community that uses it.

“Because poverty affects families differently, Poverty Stoplight breaks down the overwhelming concept of poverty into smaller manageable problems that can be solved through actions, making visible the invisible in the form of dimensions and indicators. And, families are the main protagonists in the process of eliminating poverty,” Burt explains.

“Just like personalized learning is the latest thing in education, personalized anti-poverty interventions are possible and technology like this app allows a self diagnosis,” he says. “A person can ask himself or herself questions like, ‘how am I doing with self esteem?’

Poverty and anti-poverty interventions “have been defined by the haves, not the have-nots,” Burt says. “But, the poor can define what poverty is and what poverty is not and they can come up with their own priorities on their life maps. They become self-aware, take stock and see how many green lights they have and understand the nature of their yellows and reds.”

When people have the power to name their own poverty, to call out their problems for themselves, they also have the power to do something about those problems, Burt notes. “Time and again, we have seen poor families devising solutions to problems we previously considered intractable. And, I’m not talking about solutions to reduce their poverty, or to alleviate its effects so as to make it a little more bearable, but solutions to eliminate their poverty once and for all.”

Burt devised Poverty Stoplight after having spent years researching the topic in depth, only to find that most poverty research indicators, tools and approaches focused only on measurement.

“We created a new poverty measurement tool and coaching methodology that looked vastly different to everything else available,” he explains. “I wanted our tool to be something we could use to both diagnose and address the problem. Poverty Stoplight is not just a metric, but also a framework to eliminate poverty. It helps break down poverty into bite-sized kernels, thus, making it easier to tackle.”

Incorporating subjective and social indicators embraces the humanity of poverty, Burt says. “It doesn’t reduce people to their deprivations.”

It allows governments, charitable organizations and others to devise interventions that target the greatest needs for each person in need, he says.

In "Who Owns Poverty?" Burt concludes that injustices persist when they are invisible.

“Empowered individuals make for empowered communities, and citizen activism is a powerful tool for driving the kinds of policy-level and societal change needed to make it possible for families to eliminate their poverty,” he writes. “I am poverty; you are poverty. We are all poverty and not poverty in our own unique ways. I am Martín Burt and my family has three reds and five yellows. … We are all on the same journey to do better, to get green and then keep going because we know we can and because we know it’s worth it. The world is changing. The weight of responsibility for eliminating global poverty is shifting. How will you respond?”

The following is an excerpt from his book:

What if nearly everything we thought we knew about poverty was wrong? What if the legions of policymakers, social scientists, economists, aid workers, charities and NGOs marching across the globe have been using the wrong strategy, and the wrong tactics, to wage the wrong war against poverty?

With the very best of intentions, we’ve been trying to help poor people ascend the ladder out of poverty in the name of social and economic justice. But what if we have been, as it were, leaning the wrong ladder on the wrong wall? And, what if being wrong about the problem of poverty was the only thing standing in the way of finding the solution?

Of course, this would not be the first time that society laboured under assumptions later proved to be misguided. Recall a time when educators believed that corporal punishment would ‘cure’ left-handed students, long before we understood that handedness is determined in utero. Doctors in ages past believed tuberculosis to be transmitted by vampires (and that dry air in caves, deserts or mountains was a potent cure) before scientists determined it is caused by bacteria and therefore best treated with antibiotics. Before Copernicus and Galileo, scientists believed the sun revolved around the earth.

Nor have our views on poverty itself been immune to similar debate and revision. Seeking to justify the persistent gap between rich countries and poor countries, theorists over the ages have proffered explanations ranging from the cultural to the geographical — and most everything in between.

Marxists view poverty as the inevitable result of the uneven distribution of the means of producing wealth in a society. Capitalism was created to organize production in the belief that enlightened self-interest and the logic of the market create wealth for all; it depended on a certain measure of wealth inequality to promote the entrepreneurial spirit and risk-taking behavior needed to create more jobs and more wealth (and on the view that government programs to reduce inequality only got in the way). Indeed, it’s only in recent years that we’ve started to challenge the orthodoxy of inequality as a necessary precondition for growth.

Elsewhere, the Bible assures us that the poor will always be with us, and the Protestant work ethic reminds us the poor only have themselves to blame — as wealth (the outward sign of God’s blessing) is achieved by overcoming personal, moral, intellectual or spiritual deficits. And if our hard work means we deserve our wealth, the converse must also be true: we deserve our poverty when it happens.

While these world views proffer competing narratives on why there is poverty, they are strangely silent on the question of what poverty actually is — as if, perhaps, we are meant to infer the definition from context. But surely if we’re going to get serious about the business of reducing global poverty, then we’ve got to start by agreeing what we mean by the term, right? Here, too, we witness the evolution of human understanding over time.

Book Tour

Burt will launch his book tour with a talk and book signing on campus Feb. 20. The 8 a.m. event will take place in the School of Business building, Room 5200. To RSVP, visit https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLScFQg246a-3eM2ev7G8MXRpJ3hlBJRaNlTL1b9OMBrgzH5FBg/viewform.