View of a power plant in Maharashtra, India.

New research analyzes state violence in India’s coal war

Police, who were deployed to block villagers from protesting a power plant on coastal wetlands in India 14 years ago, shot at protesters, killing three and injuring hundreds. Two years later on the other side of the country, a Buddhist monk was killed in resistance to construction of a hydroelectric dam project.

Those are just a couple of examples of state violence in the coal war in India, the country that has pledged to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2070 but also heavily relies on coal to fuel its economy.

Those are just a couple of examples of state violence in the coal war in India, the country that has pledged to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2070 but also heavily relies on coal to fuel its economy.

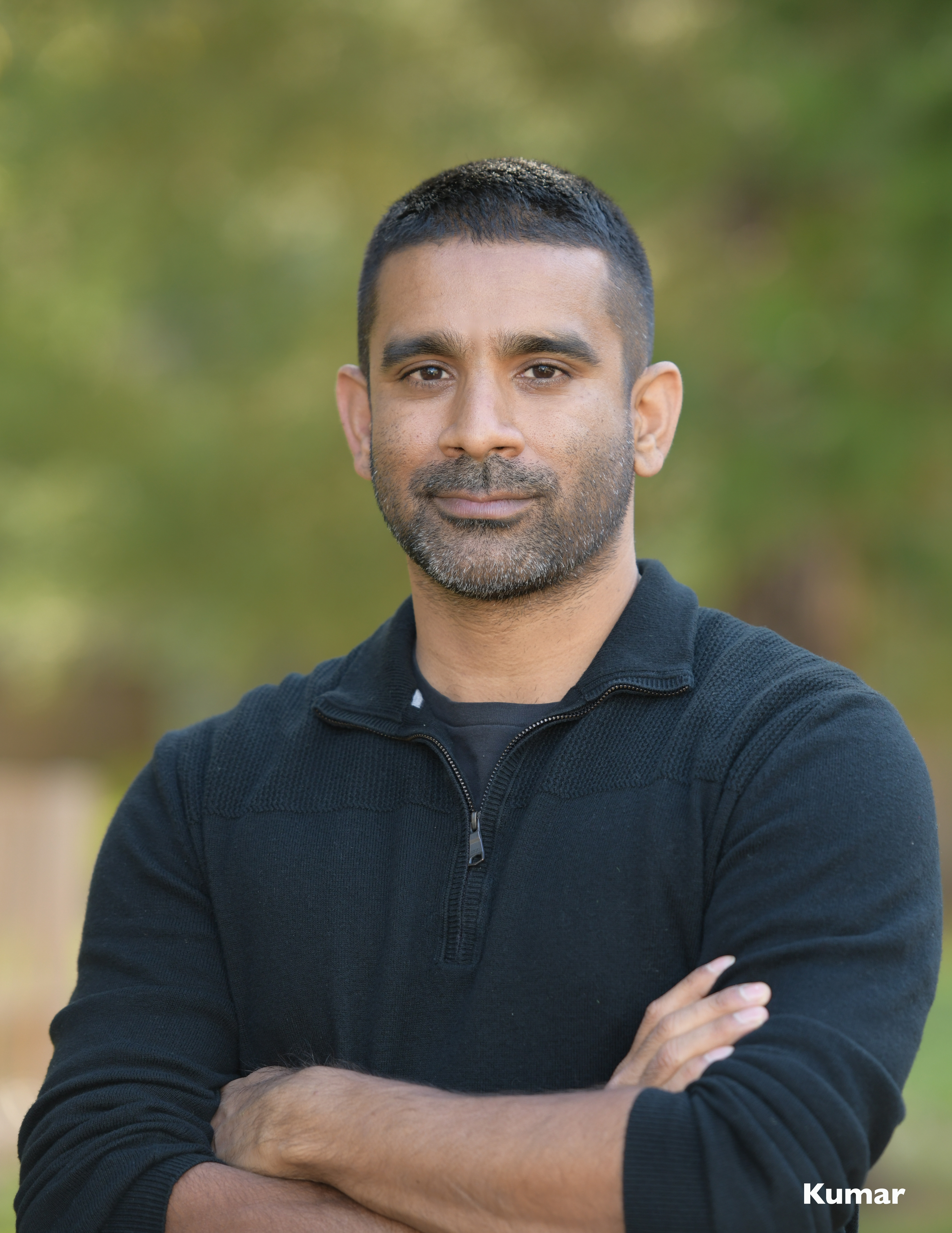

Such is the contradiction being studied by Mukul Kumar, assistant professor of urban planning and public policy.

“Debates concerning energy transitions in India have begun to pose questions of justice, drawing upon ‘just transition’ policy frameworks rooted in the Global North,” Kumar says. “The Indian Ministry of Coal, for instance, has recently announced that it will establish a World Bank-financed just transition division. Thus far, energy policy makers and researchers in India, including proponents of ‘just transition’ policy frameworks, have not paid adequate attention to the relationship between state-sanctioned violence and land expropriation, issues which disproportionately impact Indigenous and frontline communities.”

To address those issues, Kumar recently published an article in Climate and Development, analyzing what he calls “violent transitions,” which refers to the ways in which the expansion of fossil fuel and low-carbon energy infrastructures are predicated upon direct state-sanctioned violence to facilitate land acquisition.

In his article, “Violent transitions: towards a political ecology of coal and hydropower in India,” Kumar examines 121 coal and hydropower projects in India and argues that coal and hydropower energy transitions are characterized by significant state-sanctioned violence.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has declared that all coal production must be phased out by 2050 to avoid dangerous levels of global warming. Yet, India is in the midst of a fossil-fueled transition toward increased coal production, Kumar points out.

“Coal production fuels 70% of the country’s electricity-generating capacity,” he says. “At the same time, the country is also set to expand low-carbon infrastructures by an unprecedented 500 GW by 2030. The government of India is offering substantial financial incentives to develop hydroelectric dams to speed India’s ‘green’ energy transition.”

The Himalayas, for instance, have been reframed as a site for the development of more than 100,000 MW of hydroelectric dams to mitigate carbon emissions.

“Both fossil fuel and low-carbon transitions, however, draw upon forms of state violence and land expropriation to expand extractive industries,” Kumar says. “Peaceful, nonviolent movements that challenge the expansion of extractive energy industries are far too often criminalized or subjected to police violence. India is in the midst of multiple violent energy transitions toward both increased fossil fuel and low-carbon energy extraction that further marginalize Indigenous (Adivasi) and frontline communities of Dalits, landless farmers, and artisanal fishers.”

Kumar’s work analyzes the Inter-Ministerial Committee on Just Transition’s recommendations to form a Just Transition Taskforce with representatives from industries, state and regional governments, and impacted communities. But, he says, “forms of state violence, such as police violence and arrests, often preclude democratic and meaningful participation in energy policies in India. If energy transition policies fail to reckon with historical injustices of state violence and land expropriation within the context of fossil fuel and low-carbon energy transitions, 21st century energy transitions risk reproducing earlier models of extractive development that are neither sustainable nor just.”

Kumar’s article generates data to inform energy policy debates and scholarship in India. Drawing on a political ecological analysis of 64 coal projects and 57 hydropower projects in India from the Environmental Justice Atlas, he found that 51.5% of coal projects and 40.3% of hydropower projects involved mass mobilization, arrests and violence.

Kumar urges energy policy makers and researchers to “repair and redress, rather than disavow” the role of state-sanctioned violence in India’s energy transitions.

“Not surprisingly, India’s current just transition policy frameworks do not include any reference to police violence, arrests, intimidation or murders,” he notes. “Yet, for energy transitions to be truly just, histories of state violence in both fossil fuel and low-carbon industries must be acknowledged and repaired rather than disavowed. In the absence of policies that redress past histories of violence and hold police officers accountable for the criminalization of the right to dissent, just transition policies may act as another arena to legitimate the expropriation of the lands and livelihoods of Indigenous and frontline communities.”