Virginia Parks speaks at state Future of Work Commission meeting

By Mimi Ko Cruz

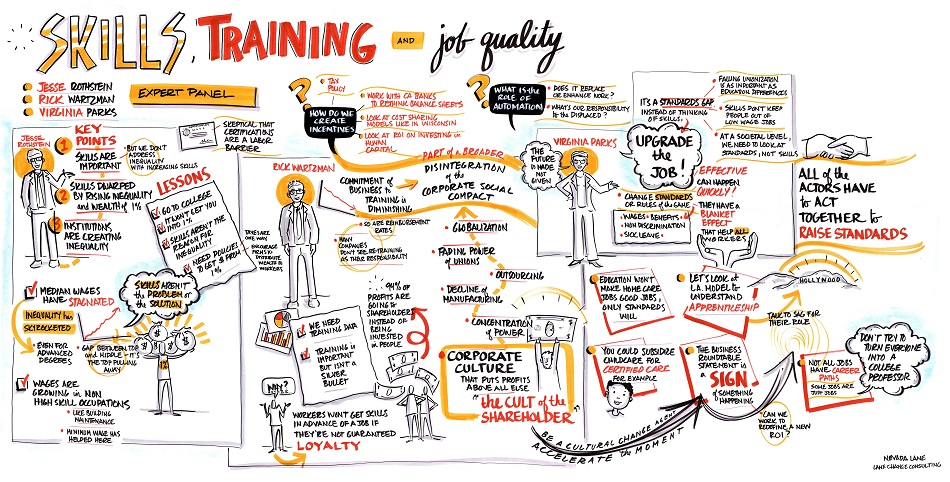

Appearing before the California Future of Work Commission, Virginia Parks, professor and chair of urban planning and public policy, made a case for closing the job standards and equity gap by upgrading jobs.

In her presentation, as part of a panel talk Sept. 10 at the commission’s meeting in Sacramento, Parks outlined how jobs should be “upgraded” to address quality, skills and equity problems in the workforce.

“Skills and training are important, but they don’t fully determine pay or conditions of work,” she said. “Quite the contrary. Decisions made by firms and policy actors about wage rates and working conditions matter. Training and education takes time. Changing job standards can happen quickly. Changing job standards has a blanket effect — they apply to everybody. This helps disadvantaged and vulnerable workers most, especially workers of color.”

A preoccupation with a “skills gap” has diverted attention away from a growing crisis in a gap in standards, Parks emphasized, adding that job standards are critical to determining employment outcomes and economic inequality.

Studies abound testing “statistical comparisons” of people who have comparable levels of education, training and job experience, but highly varying levels of pay, benefits and other conditions of work, she said. “The gender pay gap and racial wage gap dramatically illustrate this reality. If the problem was only a ‘skills gap,’ these findings wouldn’t exist.”

Parks noted a 2011 Harvard study that found that falling unionization rates as well as the growing stratification of pay by education explains the rise in wage inequality among men as differences in education.

From 1973 to 2007, hourly wage inequality grew by 40 percent. At the same time, private sector unionization rates for men fell from 34 percent to 8 percent.

For workers with a high school diploma, unionization provides greater protection from low-wage employment than would getting a college degree, Parks said, adding that the Harvard study also found that the probability of low-wage employment is reduced by 39 percent if a worker is covered by a union contract, compared to 33 percent if a worker has a college degree.

“Job creation is an intrinsically human endeavor,” she said. “People are responsible for the decisions that go into creating jobs, crafting job descriptions, setting pay rates, determining working conditions, and shaping expectations, so it’s up to policy makers and job creators to make decisions that will benefit the workers of the future.”