Racist gang profiling on the street becomes hard data, which feeds sprawling detention and deportation machine with the imprimatur of law

By Ana Muñiz

By Ana Muñiz

In the late morning, warm sun collides with cold air, shifting the proportion of each until the warmth wins. The metallic blade of a bulldozer scythes through saguaro flesh in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Everything nearby is absorbed in its rotation. It is November 2019, and the U.S. government has picked a contractor to build The Wall — or several, actually. Southwest Valley Constructors Co. received a combined $891 million from the Pentagon to dynamite 43 miles of Organ Pipe and replace it with a wall. For an additional $408 million, Southwest Valley Constructors Co. also took the San Pedro River, the ancient lifeblood of Southern Arizona. Fisher Sand & Gravel Co. received $268 million to build 31 miles of wall through the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge. BFBC, LLC won $141. 7 million to bleed the Colorado River.

The land is so beautiful and the demolition so shattering that together, they cut and soothe in almost imperceptible succession; a split followed by an immediate salve followed by another split. Monsoon storms offer temporary reprieve, blowing sections of The Wall onto its side and eroding the soil beneath. Nonetheless, despite the fight of the land and its people, it seems, at least for now, that political and law enforcement leaders have successfully deployed the specter of supposed violent cross-border criminals and gang members to justify the destruction of land for border militarization.

In my new book, Borderland Circuitry, I examine how politicians and law enforcement authorities access, interpret, and perform data in such a way as to construct immigrants and U.S.-born people of color as dangerous based on unreliable information gleaned from field interviews and informants. Tracking the evolution of various surveillance-related systems since the 1980s, I uncover how information-sharing partnerships between local police, state and federal law enforcement, and foreign partners collide to create multiple digital borderlands. I cartographically and conceptually map how collaborating law enforcement agencies have deployed digital surveillance technology to expand border control functions beyond U.S. territory, to internalize racialized control into the country’s interior, and to justify land destruction and armament along the U.S.-Mexico border.

Just as the border wall is the architecture of white supremacy, my book maps the technological infrastructure-building of white supremacy. In addition to wall contractors, the U.S. government has selected tech contractors — Palantir, Amazon, Booz Allen Hamilton, Northrop Grumman, Dev Technology Group, SRA International, and more — to build digital surveillance systems that will reinforce already existing borders, de-territorialize traditional border control methods, construct new borderlands, and criminalize racial others. The border becomes ever more hardened physically as it becomes more fluid digitally.

The border is a haunting place. I know it well; I was born in Tucson and spent the first 22 years of my life traversing the borderlands of Southern Arizona, and it won’t let me go. It is a space that is both horrific and gorgeous, full of hallucinogenic beauty and suffering.

I moved away from the Sonoran borderlands to Los Angeles in 2007, where I settled into a predominantly Black and Brown neighborhood on the cusp of the glamorous Westside. The neighborhood was, and remains, a working class community of color surrounded by mostly white, affluent areas. As I’ve written previously, this precarious geographic positioning left it vulnerable to intensive policing by the Los Angeles Police Department and to acts of borderline vigilantism by affluent residents in neighboring areas as they attempted to reinforce the urban boundary between white and other, rich and poor.

It took me only a handful of days in my new neighborhood to hear the phrase I had so often heard along the U.S.-Mexico border, said by Border Patrol agents to laborers working the earth: Where are you from? Any laborers who answered with an accent were questioned about their immigration status and, sometimes, loaded into a truck and taken away. Hazel Carby writes that the question “Where are you from?” is not primarily a question about geographic origin as much as it is an interrogation of racial belonging. You cannot look this way, cannot talk this way, and be one of us. On the U.S.-Mexico border, Border Patrol agents questioned U.S. citizen, undocumented, and lawful permanent resident workers alike. Their Latinidad marked them with a foreignness that no birthright or naturalized citizenship could counteract.

When I heard the same question — Where are you from? — in LA, it was not asked of day laborers and it was not asked by a Border Patrol agent. Rather, I turned to see an LAPD officer asking the question to a young Black man. During the next 15 years in LA, I repeatedly heard police ask this question of young men of color, and I would come to learn that it is a coded gang interrogation, a way of asking to which neighborhood, or gang, someone belongs. Questions about gang membership are really questions about race and belonging. The very act of asking is a method of racial criminalization, of inscribing criminality onto Black and Brown people, of telling people that they have stepped out of place. Like unauthorized migrants, these Black and Brown youths had transgressed a border, had dared to practice a mobility to which authorities decided they were not entitled. Though I had moved from the U.S.-Mexico border, I just ended up in another borderland.

I am in a tall, tall building, a rarity in the horizontal sprawl of Los Angeles. I’m here for a meeting, and Sofia, an immigration attorney who works for a non-profit organization that provides free legal services to undocumented people, has recently returned from court. She removes her dark blue blazer and, with an elegant drop of the wrist, places it on the back of her office chair. Leaning back in her seat, Sofia exasperatedly describes how easily gang allegations stick, “All they have to do is create a negative inference of that or make a suggestion, and then I think it becomes our burden to prove that someone is not part of any sort of gangs.” Attorneys like Sofia have to somehow prove a negative. They have to convince an immigration judge that their client is not a gang member or an “associate” — someone who hangs around with gang members — in order to keep them from getting deported.

Gang profiling is notoriously unreliable. One of the most common ways that people come to be accused of gang affiliation is by police officers on the street. Law enforcement can document someone as a gang member or associate without arresting or charging them for any crime, or even notifying them that they have been categorized as such. Officers have significant latitude in who they can label; police have considered Los Angeles Dodgers gear, Virgen de Guadalupe tattoos, oversized red or blue clothing, and someone’s presence in a “gang area” to be indicative of gang affiliation. Gang profiling depends on racial stereotyping and offers little in the way of due process protections. In heavily policed communities of color, broad groups of neighbors, family members, and friends are easily swept into the categories of gang member and associate. Gang profiling and enforcement, thus, function as a racialized legal proxy that allows police to target people of color without adequate cause or evidence.

Often the gang allegations recorded by officers on the street are entered into local or statewide gang databases. Repeatedly, gang databases have been found to be rife with misinformation, fabricated evidence, and unjustifiable entries on mostly Black and Latino men — and, in some regions like Southern California, Asian American and Pacific Islander men. In January 2020, an investigation uncovered that LAPD officers fabricated information in order to ensure that individuals fit the requisite criteria to be entered into the CalGang Database, California’s statewide list of alleged gang members and associates.

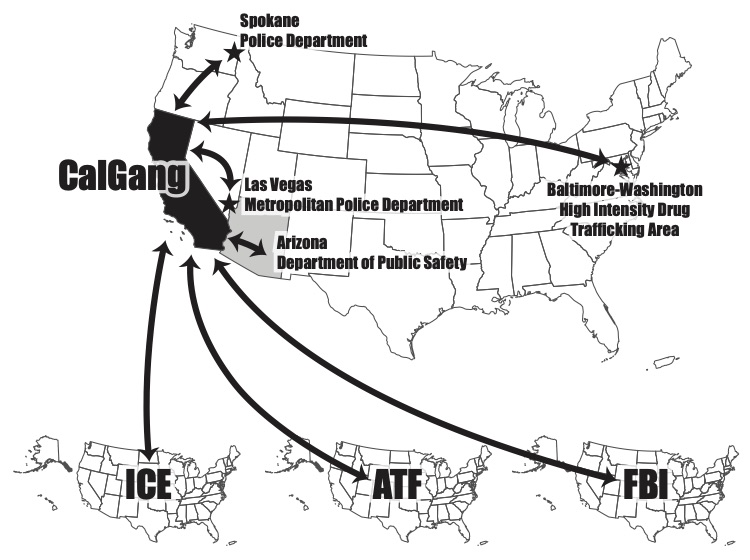

In tracing the trajectory of a gang allegation, I found that information in the CalGang Database has been shared with local law enforcement agencies in Washington state, California, Nevada, Arizona, Maryland, and Washington D.C. The result is a system of regional surveillance circuitry that targets noncitizen and American-born Latino, Black, and AAPI youth whom officers choose to profile as gang members or associates in the American West, Southwest, and, to a lesser extent, Mid-Atlantic region. Through information sharing agreements and interconnected databases, these regional circuits are then plugged into federal agencies including the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Immigration agents rely heavily on local law enforcement to identify and target alleged gang members and associates because local police possess “highly localized geopolitical knowledge” and more up to date surveillance information than do federal agents. Jeff Sessions, during his stint as U.S. attorney general, referred to local law enforcement as “the tip of the spear” in the war on gangs. Interoperable databases facilitate what I call jurisdictional buoyancy, where gang labels float up from local to federal law enforcement. Once gang-profiled people of color in targeted geographic areas are listed on local gang databases — databases subjected to little oversight and fed information by largely unchecked officers — they enter a fast track to state-level gang databases and, ultimately, federal enforcement.

Immigration agents rely heavily on local law enforcement to identify and target alleged gang members and associates because local police possess “highly localized geopolitical knowledge” and more up to date surveillance information than do federal agents. Jeff Sessions, during his stint as U.S. attorney general, referred to local law enforcement as “the tip of the spear” in the war on gangs. Interoperable databases facilitate what I call jurisdictional buoyancy, where gang labels float up from local to federal law enforcement. Once gang-profiled people of color in targeted geographic areas are listed on local gang databases — databases subjected to little oversight and fed information by largely unchecked officers — they enter a fast track to state-level gang databases and, ultimately, federal enforcement.

During our conversation, Sofia notes that ICE records will simply state that an immigrant is a “known or suspected gang member” and list the source as “database” without specification as to which database, let alone which officer, decided the classification based on which evidence. Regardless of its veracity, the allegation’s presence in a database imbues it with an authority that is difficult to counter. A cop decides someone is a gang member, writes it down, the information gets input into a database, which feeds into another database, and eventually, at the other end someone is fast-tracked to deportation. Racial profiling by police on the streets is transformed into an authoritative account that later justifies detention and deportation. This is how bias becomes hard data and how racism becomes law.

Chad Wolf, like all his predecessors, answers the border’s call and arrives at the San Diego-Tijuana line in October 2020. The acting secretary of Homeland Security poses for photos in a bulletproof vest and aviator glasses. Below the sound of cameras flashing, there is the coo of mourning doves. Wolf jumps on an ATV and revs the engine as he races along the border, the bars of bollard fencing creating a kaleidoscopic effect in the background. When he is done with his ride, Wolf will meet some of the border security contractors who contribute millions of dollars to congressional campaigns and, in return, get contracts to militarize the U.S.-Mexico border. Later, he will travel east down the border to Yuma and then to Tucson where he will tour border wall construction and see how the contractors extract millions of gallons of groundwater near sacred Quitobaquito Springs and use it to mix concrete for The Wall — between 1.7 and 3.7 million gallons for every five miles of wall.

Whenever it is politically expedient, politicians flood the border in waves, and they often talk about the specter of gangs. Wolf, for example, on a previous trip to the border, talked about an “‘exciting’ plan to go after the gangs fueling the flow of illegal migrants, weapons and drugs across the southern border.” Mark Morgan, the acting director of ICE, has come to the borderlands, too. He says that unaccompanied children are either current or soon-to-be MS-13 gang members. How can he tell? The eyes. He’s been to the border, gone into the cages, looked into the eyes of children in detention, and he just knows. Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen Nielsen visits and later claims that a family separation policy is necessary because MS-13 members are using children to disguise themselves as families at the border. President Donald Trump and Attorney General William Barr announce that the people crossing the border are not people but gang members — savages, monsters, animals.

Politicians keep showing up in the borderlands, but it remains Martian to them. This place holds none of their love stories, so they only know how to break it. They claim that the rate of alleged gang members crossing the border is skyrocketing and the only way to stop their march is to knife the water-guzzling Wall through more land and more people, fill the detention centers and databases to the brim, then build more.

To support their claims, the politicians point to data, culled from databases, that show astounding numbers of immigrant gang members in the U.S. But this clean statistical output conceals the process that leads to the allegations; a process that is shot through with equal parts incoherence, absurdity, and nefarious racial stereotypes. Gang allegations are transformed from unreliable or fabricated information into authoritative data by processing them through databases and automated assessment programs. Gang profiling and surveillance has thus emerged as a key facilitator of state violence against immigrants, particularly those from the global South, as well U.S.-born people of color, and the practice has only been aggravated by the legitimating effect of technology.

Law enforcement and politicians have bestowed a technocratic face to a devastatingly corporeal detention and deportation process in which people are reportedly raped, exposed to harsh chemicals, denied medical care, tortured, left to die, and delivered back to civil wars. It is a regime of body horror that springs from disembodied data flows. This is how all of it, the spectacularly visible — the cops, the Border Patrol checkpoints, The Wall, the politicians posing for photos on the border — and the insidiously invisible — the surveillance circuitry, the interconnected databases and automated risk assessment tools — hit the body, and the land, like a bomb.

Banner image: Nogales, AZ by Brandon Davis/Unsplash

Infographic: CalGang information-sharing agreements by Nat Case, INCase, LLC

This story was originally published in Inquest.

Watch the book trailer: