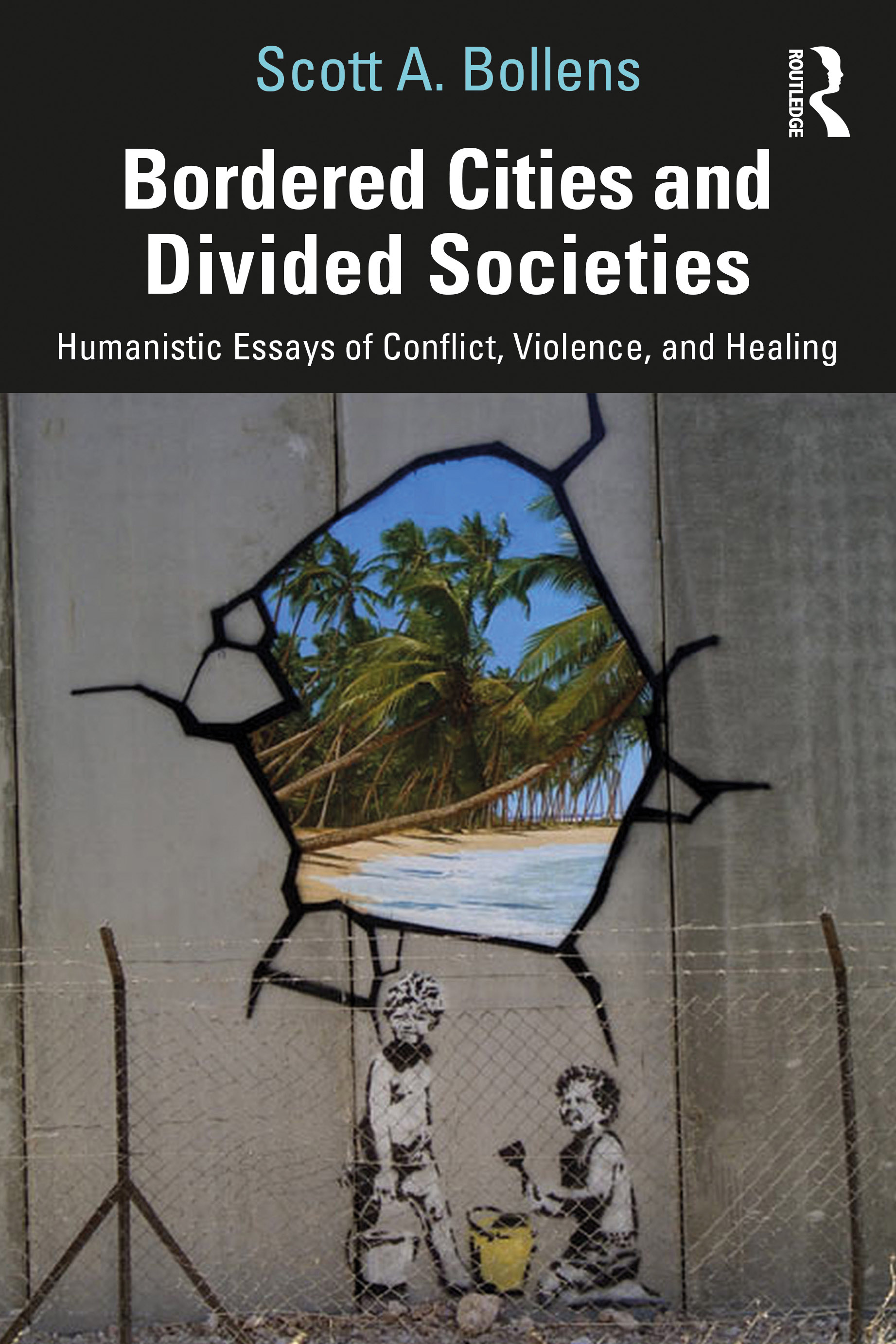

Professor Scott A. Bollens’ latest book is “Bordered Cities and Divided Societies.” Photo by Karen Tapia

New book traces lives of people living in cities of conflict and violence

New book traces lives of people living in cities of conflict and violence

By Mimi Ko Cruz

Compelling interviews of people living in places of war and conflict reveal their resilience and hope for healing in Scott A. Bollens’ new book, “Bordered Cities and Divided Societies.”

“The psychological and emotional effects and legacies of living in violent and dangerous urban environments are powerful, long lasting, and intergenerational in reach,” says the professor of urban planning and public policy and Drew, Chace and Erin Warmington Chair in the Social Ecology of Peace and International Cooperation.

The stories of his subjects, Bollens says, highlight the despair, unease and heavy psychological burdens of living and working in nine cities — Jerusalem, Belfast, Johannesburg, Nicosia, Sarajevo, Mostar, Barcelona, Bilbao and Beirut — polarized by ethnic and nationalistic animosities.

From his more than 25 years of research, Bollens has found “there is great commonality among peoples on opposing sides of conflict. Their desires and hopes often share similarities. Sadly, the dynamics of political conflict create them as antagonists and it is that larger structure that often dictates their day-to-day life. Nonetheless, Individuals often seek to rise above bare survival to engage in thoughts and actions that imagine and fight for an alternative future.”

When we categorize another person as “the other,” Bollens says, “we delegitimize and dehumanize them. When this ‘us versus them’ perception becomes inscribed into the political system, we start a downward and perpetuating cycle that erodes our collective well-being.”

His book uses an unconventional writing style that is part narrative nonfiction and part memoir.

“I wanted to delve deeper than the broader, grand narratives of politically polarized environments and focus attention on the genuine lived experience of individuals in these locations,” he explains. “During my research interviews, many of which were intimate and absorbing, I have felt present and aware that the emotional and often controversial things individuals were saying were not being absorbed by me through machine-like neutrality, but rather were interacting with my personal filter and experiences, challenges, and hopes that I had lived through in my life. Consequently, I describe human social phenomena (the ‘other’) but also provide at times a reflexive account of my own experiences (the ‘self’) in these cities and cultures.”

The following is an excerpt from “Bordered Cities and Divided Societies”:

Hope in despair, spirit amid gloom

They were 15 and 14 years old when the war started. They are now kids with the wisdom, sadness and perspective of adults. Jasmina Resulovic and Arnan Velic were 23 and 22 years old as the 20th century closed. Jasmina is a short, round faced, bespectacled young woman with contemporary flare. Arnan is a lean man, almost gaunt, dark-featured and handsome. As Jasmina says, “I guess by our parents' birth we are Muslim.” Both are architecture students at University of Sarajevo. They both stayed in the city during the four years of war, Arnan fighting in the Bosnian Army for five months, and Jasmina mired with her parents and other family in a high-rise flat near the front lines of hand-to-hand fighting. During the war, they attended abbreviated “war school” in lieu of high school. Since the war, they and a few other students now run a “getting to know Sarajevo” student project that offers tours of the historic and war affected city. I spend one and a half days alone with Jasmina and Arnan as they guide me around the city and I query them about the horrifying war years. “We grew up during the war, but we don't know when,” states Jasmina in a matter of fact way.

It is a different life now. “Everyone was equal during the war,” says Jasmina, “now money follows money.” And in a cruel irony, Arnan painfully describes how “we are looked down now by those who left during the war and now are back with new cars and clothes. Sometimes I just want to strangle them.” Jasmina's mother is a teacher and now makes about 400 DM/year, about one-third of her pre-war wages. Her underemployed father now makes less than her mother. When Jasmina was able to work as a translator for seven days, she was embarrassed to take the wages back to her household because it was as much as her mother makes in one month. Jasmina describes her interest in a book Sarajevo: Wounded City, at 109 German marks an expensive purchase. While in a bookstore on Marshall Tito Street in the city, she asks the owner who can afford such a book these days. Jasmina recounts, “The lady said foreigners and those with the big cars. Funny, isn’t it?”

Arnan's and Jasmina's story is not one of only despair. Arnan asserts in an unpredictable, almost hopeful way, “We’re not afraid of trying things now. If we fail, we fail, it’s OK. There is so much opportunity now, not compared to before the war, but in life generally. It is short and one must make the most of it.” It was not depressing during our time together to hear Jasmina and Arnan talk. By this, I do not mean that it was cheerful but rather that hearing stories of how the human soul perseveres and matures is affirmative of life. Depression relies on the lack of feeling, and this was feeling. Perseverance amidst challenge reveals the essence of who we are, scraped off of all the layers we put on it. These emotions and feelings are precious parts of life to witness, so much so that I must be careful not to want these experiences as one wants material things. Instead, I need to be grateful, always be receptive to them, for the special things they are — and what they teach about being human. There is hope in despair, a spirit amid gloom. The simple ability to persevere, live, cope, and grow amidst hatred is proof of light and love. Without the surrounding darkness, how would we know that we could illuminate each other and ourselves? Connecting to the hardship of another does not discourage, but makes one happy because it roots you in compassion.

After a day and one-half of touring war-stricken Sarajevo and tired and satisfied, I return to my hotel. At the reception desk is a gift T-shirt — of the cheap tourist type showing a curvaceous leggy woman welcoming the viewer to Sarajevo — and a note from Arnan saying this is something that may help me remember my visit. I went back to my room, lay down and was flooded by the pain and the utter goodness of people living in inhumane places and times. A boy, now man, who has lived through hell, thinks of giving to an American visitor. The kitschy nature of the gift makes it even more poignant. Sarajevo's, Arnan's, and Jasmina’s story contains a rashly different plane of emotion that overwhelms and connects one to another. Sarajevo 1999

“Bordered Cities and Divided Societies” is Bollens’ sixth book on politically polarized cities. He wrote it during the pandemic and George Floyd protests of 2020.

His students and colleagues used to ask him: “Can what occurred in the cities you study happen here?”

“With civil unrest stimulated by the George Floyd killing engulfing American cities and polarization endorsed by Trump,” Bollens says, “they are now asking me, ‘Is it happening here?’ There are disturbing similarities between the politically polarized areas of my focus and the ‘us versus them’ dynamics of American political and social life today. However, there are also assuring qualities of our system that make us different from these extreme cases. Yet, even my assurances may not be fully reassuring to you.”

Bollens holds a Ph.D. in city and regional planning and Master of urban and regional planning from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and B.A. in psychology from UCLA.

His other books include: “Trajectories of Conflict and Peace: Jerusalem and Belfast Since 1994” (2018, Routledge); “City and Soul in Divided Societies” (2012, Routledge); “Cities, Nationalism, and Democratization” (2007, Routledge); “On Narrow Ground: Urban Policy and Conflict in Jerusalem and Belfast” (2000, State University of New York Press); and “Urban Peace-Building in Divided Societies: Belfast and Johannesburg” (1999, Westview Press).

Bollens says he now is completing a dystopian, futurist novel, stimulated by his international research and the traumatic American experience of 2020.

Contact:

Mimi Ko Cruz

Director of Communications

(949) 824-1278

mkcruz@uci.edu